Inflation is very difficult to forecast

There has been considerable criticism of central bankers for making serious mistakes and not controlling inflation. Part of this is defensive posturing by governments unable or unwilling to deal with the cost of living crisis, some reflects concern amongst economists about central banks being asked to do too much – cope with the pandemic, and climate change, and the health of the financial system – thus taking their eye off the inflation ball. Mandates might change; there are press reports that Liz Truss may ask the Bank of England to abandon its 2% inflation target in favour of boosting the economy, if she becomes Prime Minister.

The Bank of England has made a series of poor inflation forecasts, although it is far from alone with such a problem. Looking back at their track record over the past months is not a pretty picture. In November 2021, CPI inflation was seen “peaking at around 5% in April 2022”; by February 2022 inflation would be “peaking at around 7.25% in April 2022”; by May 2022 CPI “may rise to in excess of 10% towards the end of the year”, whilst in its latest report it predicts headline inflation “just over 13% in Q4 2022”. Certainly many factors have been outside their control, notably the surge in energy and food prices caused by the Russia-Ukraine war and climate change, which dominate the inflation path. This is little comfort to angry households, worried businesses, concerned politicians and a critical media. Even after inflation does peak, the future path is a concern. The Bank forecasts inflation to ease slightly to 9% by the third quarter of 2023 and only drop down to the 2.0% target in the third quarter of 2024.

This week saw important inflation data from the USA, even more so after the recent employment report. Although the US economic activity is clearly slowing, the demand for labour remains high whilst health issues and early retirement have reduced the size of the available workforce. The net result was another decline in the unemployment rate in America to only 3.5%, a 50 year low, whilst triggering a further rise in average wages towards 6% from a year ago. Such a combination must worry Federal Reserve Governors – so the CPI report for July was some reassurance. The decline in oil prices has fed through to gasoline costs, helping the annual rate of inflation to come down from 9.1% to 8.5%, although core inflation excluding food and energy at just under 6% is still too high for the Fed’s liking driven by strong wage growth and firm housing inflation. The debate is still open, therefore, whether the central bank will move by 0.5% or 0.75% in September.

Longer term, the Fed must see a significant easing in the labour markets before it can halt this phase of tightening. Such an outturn is necessary for underlying inflation in the services sector to turn around. This week saw Governors such Neel Kaskari say that he hasn’t “seen anything that changes” the need for the Fed to raise rates to 3.9% by year end and 4.4% by the end of 2021, whilst inflation concerns meant Charles Evans believes the Fed will need to lift its policy rate to 3.25% – 3.5% this year and 3.75% – 4% by the end of next year. Put lower bond yields together with a weakening currency and rallying equities, and the substantial easing in overall financial conditions is exactly what the central bank does not want to see in order to reduce demand and keep a lid on inflation.

The Bank of England will also probably act again. Deputy Governor Dave Ramsden said this week “For me personally, I do think it is more likely than not that we will have to raise Bank Rate further. We know that what we’re doing is adding to an already very challenging environment. But our assessment is we need to act forcefully to ensure that inflation doesn’t become embedded”. He will be reassured too by the decline in consumer inflation expectations which is starting to be seen. Regular purchases, such purchases of cheaper petrol, matter significantly in such household surveys.

Another factor will be the state of the economy. Second quarter UK GDP data indicated a small fall of 0.1% in the second quarter, after 0.8% growth in the first. The Bank has already warned that the UK faces a bleak prospect into 2024. This chimes with the latest batch of leading indicators. The Global PMI survey’s composite output reading fell sharply to 51, its weakest reading since June 2020. Importantly, the forward-looking components of the survey weakened further, with the new orders and expected output reading slipping to their weakest levels since summer 2020.

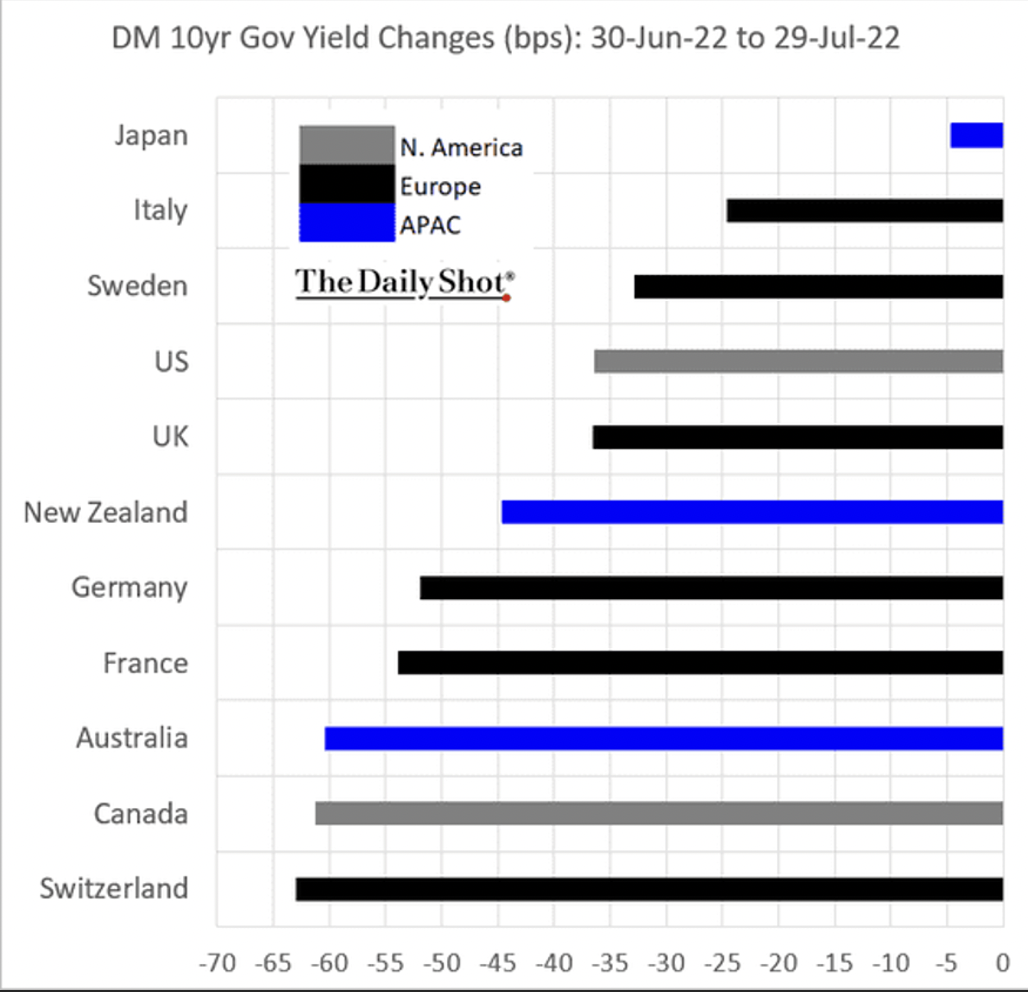

Such growth and inflation trends still encourage bond investors to expect interest rates to rise in 2022 and fall in 2023. This explains the continued inversion of the US yield curve and flattening in other countries. The US 2-10 year curve inversion is currently about 0.35% but during the week it reached 0.45%, its deepest since 2000 and before that 1981. The UK curve is noticeably flattening as well, another sign that investors expect weaker inflation and growth in the year ahead. How weak will partly depend on central bank decisions and partly on political and climate decisions outside their control.

Bond yields at the time of writing this week

% 2 year 5 year 10 year

USA 3.21 2.98 2.87

UK 2.01 1.89 2.07

Germany 0.56 0.73 0.98

Andrew Milligan is an independent economist and investment consultant. This note is offered as general commentary on economic and financial matters and should not be considered as financial advice in any form.

Andrew Milligan an independent economist and investment consultant. From 2000-2020 he was the head of global strategy at Standard Life/Aberdeen Standard Investments, analyzing the major financial markets for global clients. He currently assists a range of organizations with reviews of their investment processes, advice on tactical investing and strategic asset allocation, and how to include ESG factors into their decision making